Feature photo: Castle Rock Lake provides a staple recreational area for Colstrip residents and others from the area. Filled with water pumped in from the Yellowstone River, located thirty miles north, the man-made lake allows people to fish, swim, and relax on the water.

Left in the dark, Colstrip residents worry, still enjoy an idyllic life

Written by Amanda Garant. Images by August Schield

There’s a large city park in the center of Colstrip, Montana. If you find yourself there on a summer afternoon, sitting in the shade of an old tree, you’ll hear the sounds of this small town’s heartbeat.

Not the sounds of the Rosebud coal mine, located a couple miles west of town with its impressive draglines, massive conveyor belts and giant haul trucks. Not the sound of the power plant that shares the town’s name and currently runs at full capacity to provide 2,094 megawatts of power annually to the Pacific Northwest. Certainly not the dramatic, ominous sounds of crickets, tumbleweeds and Clint Eastwood theme-song that one imagines after reading the latest news article about the “dying” town of Colstrip — especially after the power plant’s owner announced in June, 2019 that units 1 and 2 would close that upcoming December, 30 months ahead of schedule.

Instead, you hear children’s laughter.

Nearby, dozens of kids play at the recreation center pool under the watchful gaze of teenage lifeguards. The youngsters giggle and shriek as they glide down the large water slide or jump into the deep end from the top of the climbing wall. At the adjacent splash park, parents watch their little ones pitter-patter across the soft floor, merrily cooling off in the midday sun. A group of boys search for insects and bird feathers on the manicured lawn while a handful of kiddos eat shaved ice at the playground. In the background, an occasional vehicle slowly drives by the house-lined streets as the driver heads home from work.

Those are the sounds of Colstrip.

Colstrip, Montana was born a true company town. The Northern Pacific Railway established it in 1924 and the Montana Power Company took over the mine and town in the late 1950s. Today, although coal still defines much of this community’s identity and economy, it is far more than just a company town. First and foremost, Colstrip is a family town filled with folks who are proud of their home and the lives they’ve built. It is a safe haven for growing families, for workers and for retired miners and powerplant employees.

People outside this Eastern Montana community likely put forth assumptions about this place. But if you stay awhile — if you walk those house-lined streets or visit with people over a meal — then some of those assumptions may begin to unravel.

This isn’t a dying community.

Quality of Life

If a city planner designed a dream town for 2,300 people, it would look a lot like Colstrip. It’s a safe place with high-paying jobs, affordable child care, good schools, a public library, a food bank, an active senior community and quality medical services. There is a well-used rec center, access to the outdoors, maintained sidewalks and numerous playgrounds.

“Our parks are awesome for Colstrip. The town caters to the kids,” said Mike Esser who works for the Colstrip Parks and Recreation Department. A retired telephone man, he takes care of all the parks and pathways around town, sits on the city council and helps his wife and two kids run their family’s restaurant, June’s Bungalow.

Esser and his team have their hands full. They maintain Colstrip’s 30 parks and playgrounds spread across town, mow 300 acres of green space and maintain 7 miles of paved and gravel trails. In the winter, Esser plows the paths so folks can continue to venture outside all year long.

“I love working for the parks,” he said. “As the parks, we do a lot for the community.”

On the north side of town, there’s a golf course Colstrip residents can use for free. Castle Rock Lake, just west of town, attracts residents from across southeast Montana. Owned by the Colstrip power plant and filled with water pumped from the Yellowstone River, the 150-acre lake is a popular place to spend the afternoon swimming, boating and fishing for bass, bluegill or catfish.

“I’ve had a lot of people tell me that (I) could move anywhere,” Esser said. “But I like it here.”

The Colstrip Parks and Recreation Department, a county-run entity, also manages Colstrip’s central hub: the local community center. With its long hours and wide range of programs, it caters perfectly to this town of shift-workers and young families. Colstrip residents can freely access the gym, pool, youth activities, adult work-out classes and kids’ breakfast program. Other activities charge a small fee, like $30 a semester for the kids’ after-school program.

Not many towns, big or small, can offer so many affordable services.

Not only do most Colstrip residents use the community center and its programs, but the city Parks and Rec Department is a big employer. On top of seven full-time staff, including Mike Esser, nearly 70 seasonal workers are employed. Many teens spend their summers working as lifeguards, maintenance workers or camp counselors.

During the school year, parents can rest easy, knowing their kids are in good hands. The Colstrip School District, another large employer, has an elementary school, middle school and Class B high school. The school district enrolls over 500 students, some traveling daily from Ashland or the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

The schools offer a quality education along with a variety of extracurricular activities, sports facilities, college dual-credit courses and career training classes. Local property taxes, paid mostly by the mine and the power plant, help fund these programs. Levies and grants also chip in. In 2019, Costrip public schools received a Montana Coal Board grant for $473,550 to make the high school gym Americans With Disabilities-compliant.

“The community is very supportive of the school district,” said Bob Lewandowski, school superintendent.

For the past 14 years, the community has passed every proposed levy, Lewandowski explained. That’s not typical for rural communities.

One could speculate that folks in Colstrip are willing to pay levies because they hold good-paying jobs. The median household income in Colstrip is $84,145. In comparison, the median household income of Montana is $46,972. It’s unclear what industry could move in that would be willing to pay the wages that the highly-skilled, highly-compensated population deserves. And if folks in Colstrip make less money, will they be so willing to pass levy after levy each year?

“This (coal) industry has helped create a foundation for Montana,” Lewandowski said. He expressed some concern over what would happen if the state started to chip away at some of that foundation. Ever since the owners of the power plant first announced in 2016 that two of its four units would retire, he has seen some changes.

Colstrip’s student population dropped about four percent in the last four years. That shift could affect the money the schools receive from the state, as the state funding formula is based on enrollment. The school district also hired 15 new teaches for open spots this summer — more than the typical turnover.

But Lewandowski keeps that concern at bay. His community is resilient, he said. In the meantime, he and his staff will continue to provide the kids and the taxpayers with the best education possible.

“We refuse to accept anything less than the educational quality that we offer now,” he said. “We won’t compromise and we can’t.”

Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt

As we visited with folks in Colstrip, most went about their daily lives, trying their best to maintain business as usual. Like Lewandowski and his staff, they continue to work hard and to do their jobs to the best of their ability. We never got the sense that folks are in denial about the future of their community. Residents talk about it constantly. They swap the latest rumors over dinner and share ideas for the future over coffee. Rather, folks are genuinely worried about what’s coming down the road. Time and time again, we heard that the fear, uncertainty and doubt have a greater impact on people than the actual closure itself.

Mike Esser said it best when talking about the restaurant that he and his family run: “Do I worry about (the closure of units 1 and 2)? What it would do to us? Yeah, I think about it all the time … We just keep going and we just keep feeding people.”

Their uncertainty isn’t misguided. While folks in Colstrip have worked hard to keep the lights on for millions of Americans, they themselves have been left in the dark by the people with power.

State and federal politicians regularly use Colstrip’s story as political pawns. Often, corporations make decisions without talking to or considering their employees. Colstrip workers watched in July as the Blackjewel mining company unexpectedly laid off 600 workers in Wyoming. Montanans are scared that they, too, will soon receive the dreaded pink slip. But rumors abound that the power plant won’t lay off employees; rather, the plant will more likely downsize as folks retire or leave on their own accord. The latter scenario gives people hope, even though it remains merely hearsay. The executives at the power plant, the ones who know the answers, hold their cards close to their chest — keeping their shareholders, customers and lawyers foremost in their minds.

Other folks in Colstrip believe that units 1 and 2 won’t actually close. Talen and Puget Sound Energy, two out-of-state companies that split the ownership of them, said they are closing the units early because they’re no longer making money. That perplexes workers who saw the plant running at full capacity last February in order to heat people’s homes during a prolonged cold-snap. Other residents wonder whether or not this entire announcement is a negotiation tactic between the mine and the plant over coal prices. If so, it’s a negotiation tactic that directly impacts the lives and well-being of real people.

Such rumors leave Colstrip residents in a state of limbo, unsure what actions are really coming down the pike.

In the meantime, the media — which has the ability to hold folks in power accountable — sometimes does more harm than good for the people of Colstrip. Residents say they feel vilified and misrepresented. They told Prairie Populist about reporters who come to town for an afternoon, make a few phone calls, snap a picture of the smokestack and leave without getting the full story. If and when good reporting is done, Colstrip residents remained skeptical and guarded. They’ve been burned before.

When the media reports on the power plant closing rather than the town persisting, it becomes all too easy for outsiders to assume they understand Colstrip. It’s easy to drive through this town, see a “For Sale” sign on a house and assume that the family left because of the recent announced closure of units 1 and 2. It takes time to talk to a homeowner and to learn that she and her husband have been planning their 2019 retirement for the past three years: they’re going to take their fifth-wheel, travel the country and visit their kids who have grown up and moved away. It’s easy to see an empty playground and assume through observation only that the neighborhood is abandoned. It takes energy to ask around and learn that all the kids are away at a Parks and Rec summer camp — visiting Glendive to learn about fossils. It’s easy to assume there’s no commerce because there isn’t a typical, business-lined “Main Street.” It’s important to pay attention, to drive through the grid-patterned neighborhoods of houses and note that residents run businesses out of their homes: thrift stores, barber shops or restaurants like June’s Bungalow, which I think has the best egg salad sandwich this side of the Mississippi.

Simply put, Colstrip is a community with folks who like to hunt, fish and camp with their families. It’s a town of hard-working Montanans who took high-paying jobs that challenge them and that they enjoy. It’s a community that deserves certainty.

We are All Colstrip

Here’s what is certain: the residents in Colstrip will fight tooth and nail to maintain the quality of life that they’ve built for themselves and their families. If more of us Montanans knew about Colstrip and how ingrained it is to the amenities we have across our state, then perhaps we would all come together to find a way for this community to remain viable.

America was built on coal. During World War II, trains relied on Colstrip coal to ship heavy machinery across the country and eventually overseas. It powered the settling of the west, the industrialization of the country, and the tech booms in the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Today, Colstrip is the largest power generator in Montana and second -largest coal-fired power plant in the West. Power produced in Colstrip travels via massive transmission lines across Montana before transporting electricity to Seattle, Spokane and Portland.

The electricity may be shipped out of state, but Colstrip heavily impacts Montana. Because of our state’s tax structure, taxes on coal pay for Montana’s public schools, services and infrastructure. Since the coal severance tax began in 1975, our state has made over $2 billion from the coal industry; that doesn’t include the taxes coal companies have paid to county or federal governments. In 2016 alone, coal severance tax and gross proceeds tax brought in $81 million to state and local governments. That figure doesn’t include property taxes, which brought in over $316 million, or federal royalties, 49 percent of which go back to the state of Montana. To date, renewable energy does not provide that same level of revenue as coal. But Montana has yet to invest robustly in renewables, so how the state will make up for that lost revenue is a big question mark for state lawmakers.

The changes happening in Colstrip impact all of us. A few decades ago, the people of Colstrip were American heroes who provided us with affordable energy; today, in a world increasingly concerned about coal’s impact on climate, these same folks are at times cast as villains for doing the same thing. If other Montanans think we can simply tell folks in Colstrip to find new jobs as we move along with our daily lives, then we’re the ones in denial.

Town Motto: “Tomorrow’s Town … Today”

Colstrip, the power plant and the town, was a critical part of Montana’s past. As the plant scales back, what does the future look like for Colstrip, the town, and for Montana? The townsfolk could use the support of decision makers in answering that question. So we at Prairie Populist looked at what the powers-that-be are doing to ensure Colstrip maintains its robust quality of life.

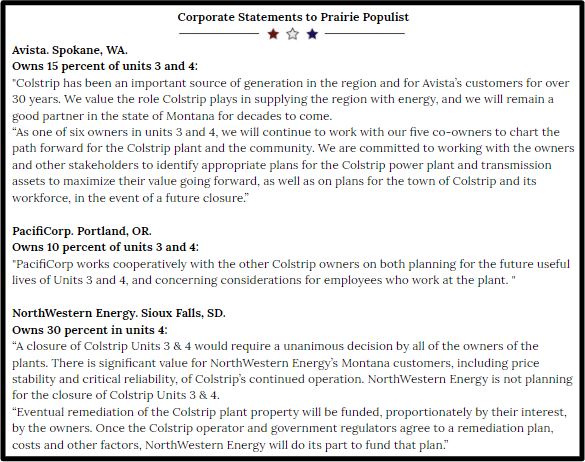

Dealing with corporations can always get a bit messy; in Colstrip, it’s much more complicated. The plant has six different corporate owners: Talen Energy and Puget Sound Energy own units 1 and 2 — the ones scheduled to close in December, 2019. PacifiCorp, Avista, Portland General Electric, Talen Energy, Puget Sound Energy and NorthWestern Energy own units 3 and 4. Westmoreland Mining LLC owns the Rosebud Mine.

Janet Kim, media relations specialist at Puget Sound Energy (PSE), which owns 50 percent of units 1 and 2, told Prairie Populist that PSE was the first of the companies to develop a funding mechanism for cleanup, dismantling and remediation. It was also the first to set aside money to assist the community in dealing with the long-term impacts of the unit closures.

PSE set aside $10 million for Colstrip after Washington state energy regulators and Montana Attorney General Tim Fox urged them to do so in 2017. The eventual $10 million community impact fund includes $7.5 million to be available to distribute to the community through grants or short-term loans and $2.5 million for a permanent endowment. Currently, a seven-member board monitors the Colstrip Impacts Foundation, which oversees the fund. The board, consisting of local community members, creates ways to accept more money from corporate or private donations, receive grant requests and distribute funds to local projects.

Talen Energy, which owns the other 50 percent of units 1 and 2, has not specifically set aside money for Colstrip’s future yet.

On July 29, 2019, Talen executives met with Montana state legislators to provide updates. The Billings Gazette reported that at the meeting, Talen Montana President Dale Lebsack told legislators that after units 1 and 2 close, they plan to keep them standing, but in “a cold, dark, dry safe condition,” until the owners are ready to demolish and remediate the entire plant. Lebsack also told legislators that they’re trying to avoid layoffs, and that uncertainty around the plant’s future is causing employees to leave on their own accord.

Talen and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1638 have been in discussion over retention, severance and collective bargaining. Rather than lay off the employees who work on units 1 and 2, Talen plans to shift workers to new tasks. People who run units 1 and 2 will either close down those units or move over to units 3 and 4.

We also reached out to the rest of the owners of units 3 and 4. Portland General Electric — which owns 20 percent of units 3 and 4 — has yet to respond. Avista, Pacificorps and NorthWestern Energy each provided a statement. Unsurprisingly, the companies expressed concern over their bottom line, the plant’s value and energy prices. But where are their plans for how these corporations will take care of the folks in this community who have given so much to them over the years?

While the fragmented ownership is complex, there are laws in place to oversee plant and mine closure. According to a 2017 report by Headwaters Economics, the owners of units 1 and 2 will need to submit a closure plan to the Department of Environmental Quality. The report said that companies must financially cover the cost of the plant closure and any groundwater clean-up. They are not responsible, however, for compensating displaced workers or paying for lost tax revenue. That is up to the local and state government.

Colstrip Mayor John Williams has lived in Colstrip since 1971, when the first two stacks opened. He is grateful to have the opportunity to serve a community that has done so much for him throughout his life.

“It’s a great place to live and work and play,” Williams said.

Williams recognizes the town’s historical and current ties to the coal industry. Everyone is either directly or indirectly involved in the plant or the mine, he said. And while he understands the impact of potential job losses, he expressed hope.

“There’s a lot of ideas of what would or could work,” he said.

Mayor Williams didn’t give specifics about what those ideas are and he admits that he and the city government have very little control over bringing in new businesses. However, he’s not sitting on his hands, waiting for someone else to solve problems.

“I can continue to provide quality services to the people who are here for as long as I can,” he said.

He will continue to work on infrastructure and to provide services so that whatever new businesses move in will enjoy nice streets, sewer, water and quality of life.

The county government’s revenues have already declined, so commissioners have been forced to increase taxes and local school levies. The good news: some industries are looking to move into Rosebud County. The bad news: per usual, everything is more complicated than it seems.

On July 24, 2019, the Rosebud County Commissioners held the first of two public meetings regarding a possible tax cut for a proposed wind farm on private land. It’s common practice for local governments to attract businesses to their locations by offering economic incentives, tax cuts and subsidies. That’s long been the case, whether it’s energy development working on our public lands or big box stores moving into our communities. But with the upcoming closure of units 1 and 2, the potential tax break didn’t land well with folks in Colstrip.

The Clearwater Wind Project, which will span three counties, has been in the works for a decade. Orion, the California company proposing the project, already poured $2 million into it, and in May, 2019, the company signed an agreement to tap into the large power lines that connect Colstrip to the Pacific Northwest. If the project comes to fruition, 300 wind turbines would produce 750 megawatts of energy. It would employ 200 to 300 workers during construction and about 25 full-time employees during operation.

“We can better compete with out-of-state wind and solar,” said Michael Cressner, who spoke on behalf of Orion at the July 24 public meeting in Colstrip city hall. “We are looking to be a long-term partner with Rosebud County.”

Sixty folks, mostly Colstrip residents who spoke out against the tax abatement, filled the room.

“As a business owner, I am definitely against a tax abatement,” said Richard Nielson, the owner of Colstrip’s Whiskey Gulch Saloon. “The loss of any revenue right now comes at us pretty hard.”

A handful of ranchers had a different take on the proposal. Without the Colstrip power plant to offset their property taxes, farmers and ranchers in rural Rosebud County pay a lot in taxes. Not many companies move in and spend millions in their neck of the woods, so they are happy to take anything they can get.

John Killen is a rancher and farmer from Angela, Montana in northern Rosebud County. He has seen too many business closures in his area. The number of equipment dealers in Forsyth dropped from three to zero; in Miles City, they’re down from six to one.

“We do need some tax relief up there,” Killen told the crowd. “We need things like this in all of Eastern Montana.”

He and the other ranchers in attendance expressed the importance of telling the rest of their country that they’re open for business.

“I think it sends a message that we would welcome new business,” Killen added.

The state, which gets a lot of its revenue from coal, also has some skin in the game when it comes to Colstrip’s future. Some state programs and grants exist to help attract businesses. However, unfortunately, the state doesn’t have a great track record of spending those funds in rural, Eastern Montana.

The Big Sky Economic Development Trust Fund, signed into law in 2005, takes interest earned from Montana’s coal severance tax and supports economic development efforts. In a recent Montana Free Press article, investigative journalist Eric Dietrich notes that most of the Big Sky Trust job grants “have been awarded with a distinctly urban skew.”

“Urban counties were awarded $33.16 per capita in job creation grants between 2005 and 2018, compared to $13.37 per capita for rural counties,” he reported.

Dietrich noted that fewer Eastern Montana businesses apply for such grants, which could account for the skewed numbers. But we at Prairie Populist wonder if more outreach and investment could be done by the state to make sure eastern Montana isn’t left behind in Montana’s job growth.

Also, the state of Montana no longer inventories available locations for commercial and industrial development. This state program previously existed. But without it, it’s hard for incoming businesses to know what development opportunities are available in Eastern Montana.

The state, however, can help with job assistance and training. Gov. Steve Bullock’s office recently allocated $175,000 from federal workforce to Miles Community College, Dawson Community College, Chief Dull Knife College and the Montana AFL-CIO. The money is meant to retrain employed or unemployed coal workers.

The federal government also awarded Montana a $4.6 million POWER grant to assist folks in coal country who have lost their jobs. The catch? Unfortunately, the state cannot access or allocate the grant until layoffs occur. It’s reactive, rather than proactive.

Governor Bullock’s office and the Montana Department of Labor and Industry are in talks with the federal government about securing potential proactive funds with fewer stipulations than the POWER grant. In the meantime, both regularly send employees from the Miles City and Billings Job Services Offices into Colstrip to help whenever possible.

Similarly, the Southeastern Montana Development Corporation (SEMDC) offers some of the most promising, proactive plans in Colstrip. Housed in town, the SEMDC serves Rosebud, Treasure, Custer and Powder River counties. The organization’s goal is to attract and support businesses with trainings, classes, grants, facilitation and loan assistance.

For example, earlier this month, the SEMDC received two federal grants specifically for coal country. The first, is a $250,000 match-grant to support small businesses in and around Colstrip. The second is for $50,000 to put toward marketing efforts. The SEMDC will combine the latter with a $25,000 state grant to re-brand and market Colstrip. Sources at the SEMDC expect to receive a few more grants shortly.

In December, 2016 — long before the announcement of units 1 and 2 closures — Colstrip residents asked SEMDC for an economic diversification plan during an annual listening session. The people of Colstrip knew intuitively what a lot of towns eventually learn: it’s stressful and dangerous to have all your economic eggs in one basket.

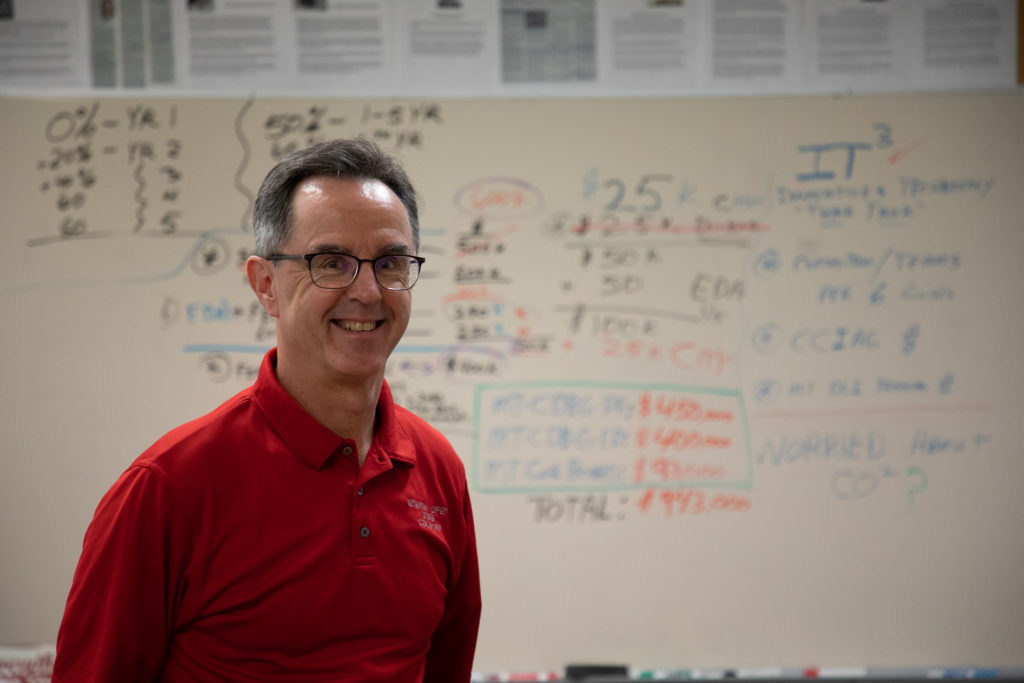

“We were never asked to focus on diversification from one community before,” said Jim Atchison, SEMDC executive director. “The community said, ‘We’ve got to do something. What can you do?’”

So SEMDC secured funding and began working immediately. After several surveys and public meetings, its study wrapped up in May, 2017. Since then, the SEMDC has hit the ground running try to implement the program.

Still, the diversification plan identified the coal industry, including cleanup and remediation, as Colstrip’s most promising possibility. Beyond the world of coal, the plan suggests high tech jobs, renewable energy, manufacturing, trade schools and agriculture. Since January, SEMDC has seen an increase in small business investment in Colstrip, including a new lumber yard, coffee shop and veterinary office. As of July, 2019, SEMDC is currently in talks with five different companies looking to move into Colstrip.

“Since the diversification plan, we’ve been pedal to the metal,” Atchison said. “We’re getting a lot of attention from Washington state to Washington DC.”

However, Colstrip faces some challenges in attracting new businesses. For one, Colstrip is located 30 miles south of Interstate 94, the major highway. The town also has limited access to clean water aside from the Yellowstone River, which is expensive to pump in, and Colstrip needs to improve its broadband capabilities. Tellingly, as for wages, Atchison also admits it will be hard to find a company that pays as well as the mine.

Yet, Colstrip the town offers great benefits to businesses compared to many other rural communities.

“If just a couple little things happened just right, Colstrip will be booming for years and years and years,” said Atchison. “All I can do is try to get companies to come and stay … We want to retain the businesses we have and attract new ones.”

As for infrastructure, Colstrip houses transmission lines, which are worth their weight in gold. New lines would be nearly impossible to rebuild today because of the price of steel and potential litigation from property owners impacted by the construction. The town also has access to a spur rail line that connects to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe rail network. It currently stores about 20 miles of rail cars, but it, too, could be reopened some day.

Nevertheless, Colstrip remains an idyllic place unlike any other Montana town. Townsfolk of all generations enjoy an incredible quality of life and most importantly, they are the most valuable resource. Not only are there hundreds of qualified, hardworking workers, but there are also families filled with passionate, caring folks who love their town.

“Every town in Montana is special because of its people,” Atchison said. But Colstrip is very unique, he added. “They’re people who will roll up their sleeves, get down to work and figure things out. “I’ll probably stay in Colstrip for the rest of my life.”

-Written by Amanda Garant. Images by August Schield

Updated August 12, 2019 at 9 a.m.

Got something to say to Prairie Populist? Send news tips, story ideas and comments to [email protected]. If you have something to submit, or an idea for a story you’d like to write for us, check out our Submission Guidelines here.