Preserving our First Capital is Worth More than Gold

Summer means exploring our state, and at Prairie Populist we’re joining the thousands of Montanans visiting the amazing lands, lakes, and historical sites that make up Montana’s state parks. We hope you’ll check back all summer and join us as we explore what these parks mean for the people of our state and how they help make Montana a place unlike any other.

Piano music of a century ago dances out the doorway of the Ryburn House — once the home of the Bannack town doctor — as if a ghost is sitting at the bench in an otherwise abandoned town, playing the music of a different era.

But it’s no apparition. Pianist Jay Christensen, a Bannack State Park regular, can be counted on for daily entertainment.

Bannack is Jay’s second home. She is at the Ryburn House most days, playing her beloved piano and talking to visitors. In fact, she is such a mainstay at the park that park employees gave her a key to the house so she can play whenever she wants. Jay comes to Bannack for the companionship of visitors and volunteers alike that she cannot find anywhere else in this remote area.

Jay is drawn to Bannack’s weathered walls, which carry the secrets of the people who lived inside them long ago, and its dusty Main Street, which once bustled with the height of the Montana gold rush. And she loves the visitors who wander Main Street today, curious about who the heck is playing show tunes.

There is something extremely romantic about Bannack. Strolling along the park’s boardwalk makes you want to throw on a long prairie dress or canvass trousers, riding boots, and a large sun hat so that you fit in with the atmosphere. The graying buildings, fading floral wallpaper, and pervasive simplicity of the area reflect the beauty of Montana’s early years of statehood.

This sentiment draws nearly a thousand volunteers, reenactors, and visitors to the ghost town for Bannack Days — a two-day event that happens every July. Full of music, carriage rides, western shootouts, and camaraderie, Bannack Days is one of the only times during the year that the park has live historians on site to help visitors with a healthy imagination bring relics back from the dead.

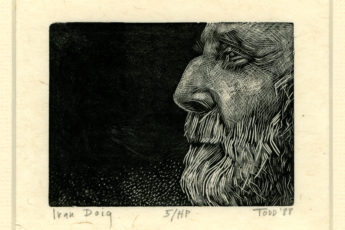

Kurt Luebke is a modern-day surveyor and surveying historian who shares Jay’s love of Bannack. He and his friend Bill arrived at this year’s Bannack Days with original surveying instruments from Bill’s personal collection, which they used to educate people about how and why the surrounding area is mapped out the way it is.

Kurt Luebke

“That is why I come back here year after year. I get to talk to people and tell them about this stuff,” explains Kurt, one of the many people from all over Montana and the rest of the country who travel to Bannack during these two special days to display trades that have been lost in time, like tinsmithing and bobbin lace making.

Bannack formed as a town in 1862, shortly after John White discovered gold in Grasshopper Creek, which runs parallel to Main Street. Soon after White’s discovery, men (and some women) arrived in droves to the middle of nowhere, as if they were swept across the plains with America’s early cattle drives, looking to strike it big on the frontier.

When Montana became a territory in 1864, Bannack was its first capital.

In its heyday, more than 3,000 people called this tiny town home. But over the years, as the area’s gold lode dwindled, Bannack dropped off the map. Without the treasured ore, Bannack, which is difficult to access and offers limited room to spread, held little draw.

When Bannack was listed as a National Historic Landmark in the 1960s, just a few persistent families still called the dying town home. When these final few residents cleared out in the 1970s, the state took over the land and created a state park.

Today, Bannack State Park is among the best-preserved ghost towns in the U.S., but such pristine and diligent preservation comes at a cost.

The Montana State Parks Foundation ranks Bannack State Park as the most at-risk park in the state due to recent funding cuts. Preserving and maintaining the buildings is difficult and costly, a challenge compounded by the looming threat of flash floods that occasionally pour through Main Street from Grasshopper Creek.

When a building is in need of repair, the park cannot call in any contractor. Only a historical preservation specialist familiar with 20th-century log homes and chinking has the skills to get the job done right. And that work is not cheap. Down the street from the Ryburn House sits the famous Hotel Meade. Inside the hotel, a sign details the $200,000 restoration project completed at the site just last year. The building still has holes in its ceiling and walls, because there is just not enough money to complete all the needed repairs.

As the upkeep becomes harder each year, Montana State Parks is working to find creative ways to continue Bannack’s legacy. Fortunately, Bannack enjoys the support of a wide community of people who cherish it, including historians, volunteers like Jay and Kurt, and the Montana State Parks Foundation. Through sweat equity and financial contributions, this quiet but mighty historical community is working hard to keep Bannack State Park’s mother lode spirit alive.

—Brooke Reynolds

Photos by August Schield.

Bannack Days is a two-day event that happens each year over the third weekend of July thanks to the large effort of the Fish, Wildlife and Parks staff as well as United States Americorps. It is a family-friendly event and features historical presentations, musical performances from residents of the surrounding communities, live demonstrations, good food, and more.

Got something to say to Prairie Populist? Send news tips, story ideas and comments to [email protected]. If you have something to submit, or an idea for a story you’d like to write for us, check out our Submission Guidelines here.

Edit: Bannack Days is one of two events of the year that includes live historians, not the only event.